Posts Labeled News

MU scientists find that plants use chemical signaling in stress response

January 21, 2014Newly Discovered Receptors in Plants Help Them Recover from Environmental Changes, Pests, and Plant Wounds, MU Study Shows

January 16, 2014Extracellular ATP receptor found in plants

January 16, 2014Scientists Report First Step Away From Fertilizers

November 20, 2013Scientists Report First Step Away From Fertilizers

By XiaoZhi Lim (Original story)

BU News Service

Nodules – small, rounded bumps – on the roots of a soybean plant. These nodules contain nitrogen-fixing bacteria that can produce nitrogen compounds from atmospheric nitrogen for the plant. Photo courtesy of user Terraprima on Wikimedia Commons.

Before synthetic nitrogen fertilizers existed, plants and bacteria worked together to return nutrients to the soil. A type of bacteria living in plant roots, called nitrogen-fixing bacteria or Rhizobia, enriches the soil with nitrogen from the atmosphere, making it available to the host plants. But not all plants can host Rhizobia, because the plants’ immune systems repel the bacteria. Scientists have long believed that only legumes, or plants like soybean, pea, and alfalfa, could chemically communicate, and therefore accept, the nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

Gary Stacey, Professor of Soybean Biotechnology from the University of Missouri. Photo courtesy of Gary Stacey.

Recently, Gary Stacey and his team of researchers from the University of Missouri found that that might not be true. In an article from Science, Stacey and his group reported that legumes are not the only ones that can chemically communicate with Rhizobia. Their finding eventually could be important to farmers as a viable alternative to synthetic fertilizers.

In centuries past, farmers used manure or crop rotation to introduce nitrogen in the soil. They would spread limited quantities of manure on their fields, or plant legumes in between crops like corn or wheat to replenish nitrogen. With the development of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers about a century ago, getting nitrogen to plants became much simpler and more reliable than spreading manure or crop rotation. But synthetic nitrogen fertilizers created problems such as water pollution.

Scientists like Stacey have recognized that if they can figure out how the relationships between Rhizobia and legumes work, they can begin to expand the use of this 60-million-year-old partnership in farming.

The relationship between Rhizobia and legumes begins with an immune response, or the lack of one. As Rhizobia approaches plant roots in the soil, the plants treat Rhizobia as a threat and activate their immune systems. Rhizobia then sends out chemical messages that the legumes recognize, called Nod factors. The target plants withdraw their defenses and let Rhizobia infect them. The infection triggers a sequence of events that leads to Rhizobia settling inside special nodules in the legumes’ roots. From there, Rhizobia produces nitrogen for the legumes while the legumes provide food and shelter for Rhizobia.

For decades, scientists believed that non-legume plants like corn, wheat and tomatoes could not work with Rhizobia because they did not respond to the chemical messages and lower their defenses.

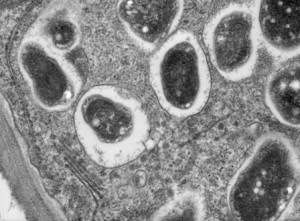

A transmission electron microscope image of the cross-section of a root nodule, showing the nitrogen-fixing bacteria living within plant roots. Image courtesy of Louisa Howard, Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility on Wikimedia Commons.

Stacey and his research group learned otherwise, by accident, when they were studying plant immune responses. They showed that Arabidopsis, a non-legume plant commonly used in biological models, responded to Nod factors and lowered its immune defenses. This response was overlooked as it was commonly accepted between scientists that non-legumes could not recognize Nod factors, according to Katherine Gibson, a plant biologist at University of Massachusetts Boston. They also found similar effects with corn and tomatoes — signs that non-legumes can understand Rhizobia’s messages. Furthermore, with Arabidopsis, Stacey and his team identified a plant receptor that was highly likely to be responsible for recognizing Nod factors. “This is a very exciting finding,” said Gibson, explaining that a wider group of researchers studying plant immune responses would be interested in the receptor.

While Stacey’s findings brought researchers one step closer to understanding the Rhizobia and legume partnership, there is still a long way to go until a practical application of their research is available for farmers. Even though Stacey and his team found that Arabidopsis, corn and tomatoes all understood Rhizobia’s messages and lowered their immune responses, that only led to a small, localized infection, instead of triggering changes in the plants’ roots for Rhizobia to settle in. “That’s the step we need to focus on,” said Stacey. With further research, scientists like Stacey can help drive modern agriculture’s dependence on chemical fertilizers back to biological, benign ways to fertilize the soil.

Dr. Gary Stacey will give a talk at the 18th International Congress on Nitrogen Fixation in Miyazaki, Japan

September 24, 2013A presentation will be given by Dr Gary Stacey on “Application of model plants and functional genomics to the study of early symbiotic signaling” at the 18th International Congress on Nitrogen Fixation in Miyazaki, Japan from 14-18 October, 2013. Click here to the official website of the 18th International Congress on Nitrogen Fixation for details.

The secret of the legume: Bond Life Sciences Center researchers pinpoint how some plants fix nitrogen while others do not

September 11, 2013The secret of the legume: Bond Life Sciences Center researchers pinpoint how some plants fix nitrogen while others do not (By Roger Meissen)

Yan Liang and Gary Stacey research the symbiosis between legumes, like these soybeans, and nitrogen-fixing bacteria at the Bond Life Sciences Center

A silent partnership exists deep in the roots of legumes.

In small, bump-like nodules on roots in crops like soybeans and alfalfa, rhizobia bacteria thrive, receiving food from these plants and, in turn, producing the nitrogen that most plants need to grow green and healthy.

Scientists have wondered for years exactly how this mutually beneficial relationship works. Understanding it could be the first step toward engineering other crops to use less nitrogen, benefitting both the bottom line and the environment.

University of Missouri Bond Life Sciences Center researchers recently identified what keeps crops like corn and tomatoes from the sort of symbiotic relationship enjoyed by legumes. Science published this discovery online Thursday, September 5, 2013.

“Our work uniquely shows that all flowering plants, not just legumes, actually do recognize the chemical signal given off by rhizobia bacteria,” said Gary Stacey, Bond LSC investigator and plant sciences professor.

His lab identified the most likely receptor for this chemical and showed that the signal suppresses the plant immune response, which normally protects plants from pathogens. This allows rhizobia a better chance to infect and live inside the plant.

Grounded

Chemical signals are extremely important to plants.

Since plants can’t walk around to explore or avoid danger, receptors in cells of each plant act as its eyes and ears. They gather information about insects, bacteria and other threats and stresses from chemicals. These signals allow the plant to respond and adapt to its environment, such as resisting stresses like drought and infection by pathogens.

With rhizobia, the bacteria produce lipo-chitin, a sugar polymer with a fatty acid attached. This molecule is similar to chitin normally found in the cell walls of fungi, the exoskeletons of crustacea or insects.

Legumes, such as soybean, sense this signal – called a NOD factor since it triggers nodulation – and create the nodules where the bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil.

That doesn’t happen in other plants.

Two possibilities

Scientists once gravitated toward thinking that non-legumes, which are not infected by rhizobia, just weren’t capable of receiving the NOD factor signal. But, a less popular theory guessed that plants like corn do receive the NOD factor signal but interpret it differently or have a problem with the mechanistic pathway.

Stacey said figuring out which is happening is like fixing a motion-detecting light.

“If you walk into a room and the light doesn’t turn on, either the motion detector is broken or there’s a breakdown of the electrical circuit between the detector and the light bulb,” Stacey said. “The analogy in a corn plant would be that it either doesn’t recognize the signal or recognizes the signal but lacks the ability to couple it with downstream developmental effects.”

Stacey’s lab set out to determine which was true.

Corn, soybean, tomato and Arabidopsis were treated with bacterial flagellin, a protein known to cause a strong immune response, and also received doses of the NOD factor. These represent a diverse spectrum of plants to ensure the results were wide ranging. Results showed the NOD factor suppressed the immune response by 60 percent.

“After these results, what allowed us to take the next step forward is that we were able to make mutant plants with changes in what we think is the receptor for the NOD factor,” Stacey said. “That step showed that when plants lack the ability to recognize the NOD factor, you don’t see the suppression of the immune system.”

Since all plants seem to respond to the NOD factor, scientists think this immunity suppression ability could be evolutionarily ancient and part of how rhizobia bacteria changed from foe to a symbiotic partner.

“There’s this back and forth battle between a plant and a pathogen,” said Yan Liang, an MU post doc in Stacey’s lab. “Rhizobia eventually developed this chemical to inhibit the defense response and make the plant recognize it as a friend.”

A future in the field

Nitrogen has both an environmental impact and high price tag.

Fossil fuels are combined with nitrogen from the atmosphere to create the fertilizer.

When applied to fields, the excess fertilizer also ends up in rivers and streams, contributing to nitrification and hypoxia in waterways.

“The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is generally attributed to agricultural runoff and producing nitrogen fertilizer increases dependence on fossil fuels,” Stacey said. U.S. farms used almost 13 million tons in 2011, according to the USDA, with almost half of it being applied to corn. Nitrogen prices ranged from $400-$850 per ton in the U.S. in 2013.

Nitrogen fixed in the soil by rhizobia is the closest thing to a free lunch a plant can get. For farmers, that’s one less input needed and is part of why legumes remain a staple of crop rotations.

In 2012, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation donated $10 million to the John Innes Center in Norwich, United Kingdom, to study and develop symbiotic relationships between bacteria and cereal crops, most notably corn. It hopes to bolster subsistence farming in Africa through the five-year project.

While it’s a long way off, Stacey’s research is another step to improving crops.

“Since the discovery in 1888 of this nitrogen-fixing symbiosis between this bacteria and plants like soybean, the dream has always been to transfer this technology into other plants like corn, wheat or rice,” Stacey said. “Once we understand exactly what’s mechanistically unique in a legume, then we hope to be able to transfer that trait into corn many years down the road.”

(Click here to Original Story by Roger Meissen)

A new paper of the Stacey Lab has just been published in Science Express

September 9, 2013Nurturing Future Plant Biologists: Two High School Students Joined the Stacey Lab for Summer Internships

August 2, 2013Cultivating a Better Botany Course for High Schools

July 15, 2013(Click here to the original story at the NSF website)

High-school biology teachers are delving deeper into the plant world with the help of plant biologists at the University of Missouri. Through professional development workshops, the teachers learn concepts in plant biology from research scientists and receive curricular materials aligned with state and national science teaching standards.

Caption: Teachers extract DNA from plants during a workshop.

Credit: Laurent Brechenmacher, University of Missouri

This program is unique in that it incorporates aspects of basic scientific research into an engaging plant biology program for teachers, and emphasizes an investigative approach for classroom learning. In addition, the program has the teacher participants return to the workshops so they can share their experiences and gain additional insight into plant biology.

Caption: Teachers gain insights into plant anatomy and physiology.

Credit: Deanna Lankford, University of Missouri

Teachers learn how to extract DNA from plant materials, examine nodule formation in soybeans roots inoculated with the bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and create biofuels from plant oil. The teachers receive background information and student-ready investigations for each of the concepts emphasized within the program. They also receive soybean seeds, planting materials and a light set to support implementation of the investigations when they return to their classrooms.

Caption: Teacher create and test biofuels.

Credit: Laurent Brechenmacher, University of Missouri

In addition to conducting the teacher workshops, the researchers have recruited and mentored undergraduate students in plant science research. Through the Freshman Research in Plant Science program, faculty mentors invite first-year students to work in their labs for 8 to 12 hours per week during the academic year. The students also attend weekly meetings led by a senior graduate student who engages them in discussions, presentations and other activities designed to enhance their experiences with plant science research.