An Unexpected Path – Plant sciences student strives to obtain an education for the greater good

Written by Jacob Shipley · October 13, 2017

Link to original story with photos

When Adama Tukuli, doctoral student in the Division of Plant Sciences, was growing up in Metahara, Ethiopia, attending school was not commonplace.

“They love their kids and do everything they can for us, but they just don’t understand education is something we need,” Tukuli said.

He was still young when he met a man who had attended school and became an engineer. Tukuli viewed him as a role model and grew determined to make education a priority.

In a primarily agricultural economy, children are usually required to stay home and assist with the farm. This meant that Tukuli had to convince his family to let him leave the cattle so he could attend school during the day. It did not help that school was 20 kilometers (12 miles) away.

Tukuli’s parents allowed him to attend, but the work on the farm did not disappear. He would run to school early in the morning, attend class, run home and then work late nights back at home.

Years and many unexpected events later, an education is still a top priority for Tukuli.

Lighting a spark

It was in ninth grade civics class when Tukuli first heard of impending agricultural problems associated with the global population growth. Growing up on a farm, he was surprised to learn that it may soon be a struggle to feed everyone on the planet. Tukuli said this was the event that lit his lasting passion for plant sciences.

He began his college career at Jimma University in Jimma, Ethiopia, and quickly became involved in the student association working with the community, raising awareness for HIV and more. As a senior, he became president of the organization.

During the summer following Tukuli’s junior year, he received a horticulture internship in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. While working with local rose growers, he discovered that their main cost was paying for coco peat, a medium to germinate the roses. This piqued his interest and resulted in further research during his senior year. Tukuli noticed that fermented coffee pulp looked very similar to the coco peat and thought it was worth trying. The results were promising.

“That byproduct (coffee pulp) that no one was using, a pile the size of this building, now became usable,” Tukuli said.

His invention germinated the roses even better than the coco peat. Tukuli and the student association freely shared this newfound information with the farmers, resulting in a quick friendship.

“They loved me and I loved them,” Tukuli said.

After graduating top-three in his class, Tukuli temporarily stayed at the university as an employee, but soon applied for a scholarship, and ultimately left to pursue a master’s degree, at Leibniz University of Hanover in Germany.

During summer break after his first year at the university, he reconnected with an old friend, Fatuma Hullo. Tukuli and Hullo had known each other since high school, but now sensed something more than a friendship. The two married prior to Tukuli heading back to school.

Unquenchable flame

During the second year of his studies, news broke out from Ethiopia. The student organization that Tukuli had been a part of was under attack from the government. The farmers that they had been working with were protesting against the government and the student association was under suspicion of colluding with them.

Tukuli said the organization had simply been helping the farmers grow roses and teaching them about the importance of education.

“To the best of my knowledge, we didn’t do anything bad,” Tukuli said. “All of my friends, the student association members, they got jailed – some of them killed.”

Knowing he was unable to return to Ethiopia, Tukuli recalls telling one of his professors, “I’m not even able to continue my education. I just want to get a stable life first.”

Tukuli fled to the United States in search of asylum and stayed with a friend living in St. Louis, Missouri. He was granted asylum in November of 2011. Tukuli’s wife was able to leave Ethiopia and join him in the United States as part of the “family reunion” program for asylum recipients.

Once approved to work, he found a job as a cashier and soon after as a lab technician at Monsanto in Chesterfield, Missouri, where he worked for the next two years.

In 2015, Tukuli had resided in the United States for five years without a criminal record, making him eligible to apply for citizenship. Through studying for the required test, he learned about the country’s history and became intrigued.

“When I was applying for my citizenship I came to learn a lot,” Tukuli said. “This country saved my life so I decided to serve.”

Tukuli enlisted with the Army Reserve and was stationed with a unit in St. Louis. He will remain enlisted until 2023.

Fanning the fire

Despite the detour, education was never far from Tukuli’s mind.

“That was a transition time for me to establish myself,” he said. “My plan was still to become a student.”

Tukuli took a leap of faith and left the attractive pay at Monsanto to come to Columbia with dreams of getting a doctorate. Henry Nguyen, Curators’ Professor of Plant Sciences, found him a spot as a lab technician working in his molecular genetics and soybean genomics laboratory. Tukuli used the employee tuition assistance program to work on graduate classes, taking one class per semester to avoid student loans.

James Schoelz, professor in the Division of Plant Sciences, taught one of Tukuli’s classes and the two kept in touch. They eventually found a way to get Tukuli back in school full-time. With Schoelz’s help, Tukuli applied for a position working as a lab technician in the Stacey Lab and for a fellowship to fund his education. In August, he began his first semester as a full-time Ph.D. student. Because of previous coursework, Tukuli is able to focus the majority of his time and effort on research.

“It’s a good program – I like it,” Tukuli said. “Most of the professors are really helpful. They are nice and have good advice. The professors work as a team to produce tomorrow’s leaders in science. I recommend this program to anybody who wants to study plant science.”

Minviluz (Bing) Stacey, assistant research professor in the Division of Plant Sciences, recalls getting the call asking to find Tukuli a spot in her lab as a technician.

“I really didn’t have that much money, but I said ‘I can talk to him,’” Stacey said. “He really wanted a Ph.D. and I wanted to give him the chance.”

Stacey was impressed with his dedication to taking classes and pursing an education amidst his difficulties. Ultimately, she was able to find him a spot.

“He is very positive and very kind,” Stacey said. “He’s always willing to help.”

In addition to cooking up Ethiopian cuisine for the lab parties, Tukuli joined other students and visited Stacey’s home while she was ill. He said he is thankful for the role that both Gary and Bing Stacey have played in helping him in the transition to become a full time Ph.D. student.

Since ninth grade civics class, much has changed for Tukuli. In addition to playing the role of lab technician and student, he has the title “dad” to Bilisummaa (4) and Nimoona (2). Despite his growing family in the United States, he is unable to visit his family back home so long as the current government is in power.

While not running to and from school anymore, he still finds time to train for his health and for the Army. After returning from basic training, he overheard about a Columbia staple, the Turkey Trax, a Thanksgiving Day race. He entered and won his age division. Tukuli is also a member of the graduate professional council for the Department of Plant Sciences Graduate Student Association.

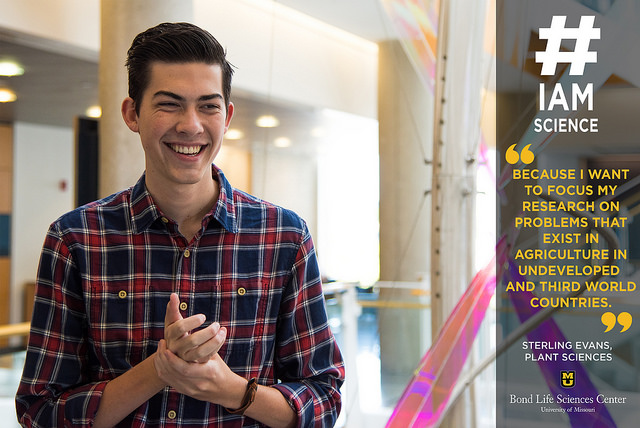

The root of Tukuli’s drive remains steadfast.

“When I say I study plant sciences, it’s personal to me. I’ve been through a lot in Africa and I know people are suffering from shortage of food. Now, I am living in the developed world with my family where people want quality food, so food quantity and quality is personal to me.” Tukuli said. “I just want to work on plants and cure the quantity and quality problem. I think it’s the right thing to do and I believe in that and I want to do that.”